| Projects: |

Works:

Prose

• Τρεις χιλιάδες χιλιόμετρα (Three Thousand Kilometers), short stories, 1980

• Ο τελευταίος σεισμός (The Last Earthquake), novel, 1985

• Το ελληνικό φθινόπωρο της ΄Εβα-Ανίτα Μπένγκτσον (The Greek Autumn of Eva-Anita Bengtsson), novel, 1987

• Η σκόνη του γαλαξία (Galaxy Dust), novel, 1991

• Η νοσταλγία των δράκων (The Nostalgia of Dragons), novel, 2000

• Τι ζητούν οι βάρβαροι (What the Barbarians Are Asking For), novel, 2008

• Λαχανόρυζο του Σταυρού (Post Summer Delights), short stories, 2012

Moreover, several short stories are included in theme anthologies or published in newspapers.

Essays, aphorisms, literary criticism

• Ημεδαπή εξορία (Exiled in the Native Country), essays and reviews, 1991

• Αντιλεξικό νεοελληνικής χρηστομάθειας (Anti-lexicon of Modern Greek Chrestomathy), aphorisms, 1994

• Έλληνες μεταπολεμικοί συγγραφείς (Greek Postwar Writers), guide, 1995

• Τετέλεσται (It Is Accomplished), essays on photographic documents, 1996

• Στις καθυστερήσεις του ημιχρόνου (In the Extra Time of the First Half), essays and aphorisms, 1999

• Η θέα πέρα από τον ακάλυπτο (The View Beyond the Lightshaft), essays and reviews, 2002

• Ελληνικό hangover (Greek Hangover), essays, 2005

• Η νοσταλγία της πραγματικότητας (Longing for the Reality), essays and reviews, 2015

• Το Νέο Αντιλεξικό νεοελληνικής χρηστομάθειας (The New Anti-lexicon of Modern Greek Chrestomathy), aphorisms, 2019

• Η ελιά και η φλαμουριά (The Olive and the Lime), a panorama of Greek literature 1974-2020, 2021

Treatises

• Η ελληνική διανόηση στον κινηματογράφο (Greek Intellectuals as Filmmakers), 1979

• Η εξέλιξη της ανθρώπινης σεξουαλικότητας (The Evolution of Human Sexuality), doctoral dissertation, 1986

• Συγκριτική ψυχολογία (Ηθολογία) (Animal Behaviour), 1994

Translations

Among the 63 books, both fiction and non-fiction, that he has translated are works by Daniel Defoe, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, E.T.W Hoffmann, Lord Byron, Giacomo Leopardi, Edgar Allan Poe, Jules Verne, Algernon Blackwood, Bertolt Brecht, Daphne Du Maurier, Karel Čapek, Jens Bjørneboe, Veijo Meri, Eeva Kilpi, Martti Joenpolvi, Erich Fried, Wolf Biermann, Julian Barnes, Peter Høeg et al. He has also edited anthologies of German short stories, Finnish short stories and Finnish poetry, and he has translated poems of Desmond Egan, Inger Christensen, Henrik Nordbrandt, and Doris Kareva. Non-fiction authors translated by him include Ibn Khaldun, Max Weber, Walter Benjamin, Egon Friedell, Werner Heisenberg, John Maynard Smith, Siegfried Kracauer, Paul Klee, Herbert Marcuse, Ernest Borneman, Hans-Georg Beck, E.J.Hobsbawm and many others.

His works in translation:

In French:

• Poussière d’ étoiles, translator: Jasmine Pipart, Hatier, 1994

• La Nostalgie des Dragons, translator: Caroline Nicolas, Actes Sud, 2004

In German:

• Der griechische Herbst der Eva-Anita Bengtsson, translator: Gaby Wurster, Dialogos, 1989

• Griechische Schriftsteller der Gegenwart, translator: Doris Wille, Romiosini, 2000

• Die Mumie des Ibykus (Die Nostalgie der Drachen), translator: Gaby Wurster, Reclam-Leipzig, 2002

• “Der andere Pfad”, translator: Sophia Georgallidis, in: Niki Eideneier, Sophia Georgallidis (ed.), Die Erben des Odysseus, dtv, 2001

• “Und trotzdem”, translator: Maria Petersen, in the journal Metaphora, Nr 7, 2001

• “Physalia kalliauchen”, translator: Sophia Georgallidis, in: Sophia Georgallidis (ed.), Ausflug mit Freundinnen, Romiosini, 2002

In English:

• It Is Accomplished (excerpt), translated by the author, in: Greek Writers Today, Hellenic Authors’ Society, 2003

• “The Other Footpath”, translator: David Connolly, in: David Connolly (ed.), The Dedalus Book of Greek Fantasy, Dedalus, 2004

In Danish:

• Eva-Anita Bengtssons græske efterår, translator: Vibeke Espholm, Husets Forlag, Århus, 1995

In Swedish:

• Eva-Anita Bengtssons grekiska höst, translator: Cecilia Wedmark, Aegis Förlag, Lund, 1998

In Czech

• “Druha cesta”, translator: Alexandra Buchler, in: Alexandra Buchler (ed.), Cerne olivy, Apsida, 2000

In Romanian:

• Nostalgia demonilor, translator: Elena Lazar, Editura Omonia, 2001

In Serbian:

• Nostalgija zmajeva, translator: Gaga Rosić, Prosveta, 2003

In Bulgarian:

• “И все пақ”, translator: Здравка Миҳайлова, in: Да oпoзнaeм своймe сүседи, Центар за Образователни Инициативи, 2002

• Носталгията иа змейовете, translator: Здравка Михайлова, Балкани, 2007

In Hebrew:

• [Η νοσταλγία των δράκων], translator: Amir Tsukerman, Tel Aviv, Keter, 2012

In Polish:

• A jednak, translator: Dorota Jędraś, nowogreckablog.wordpress.com, 2016

|

| Abstract text: |

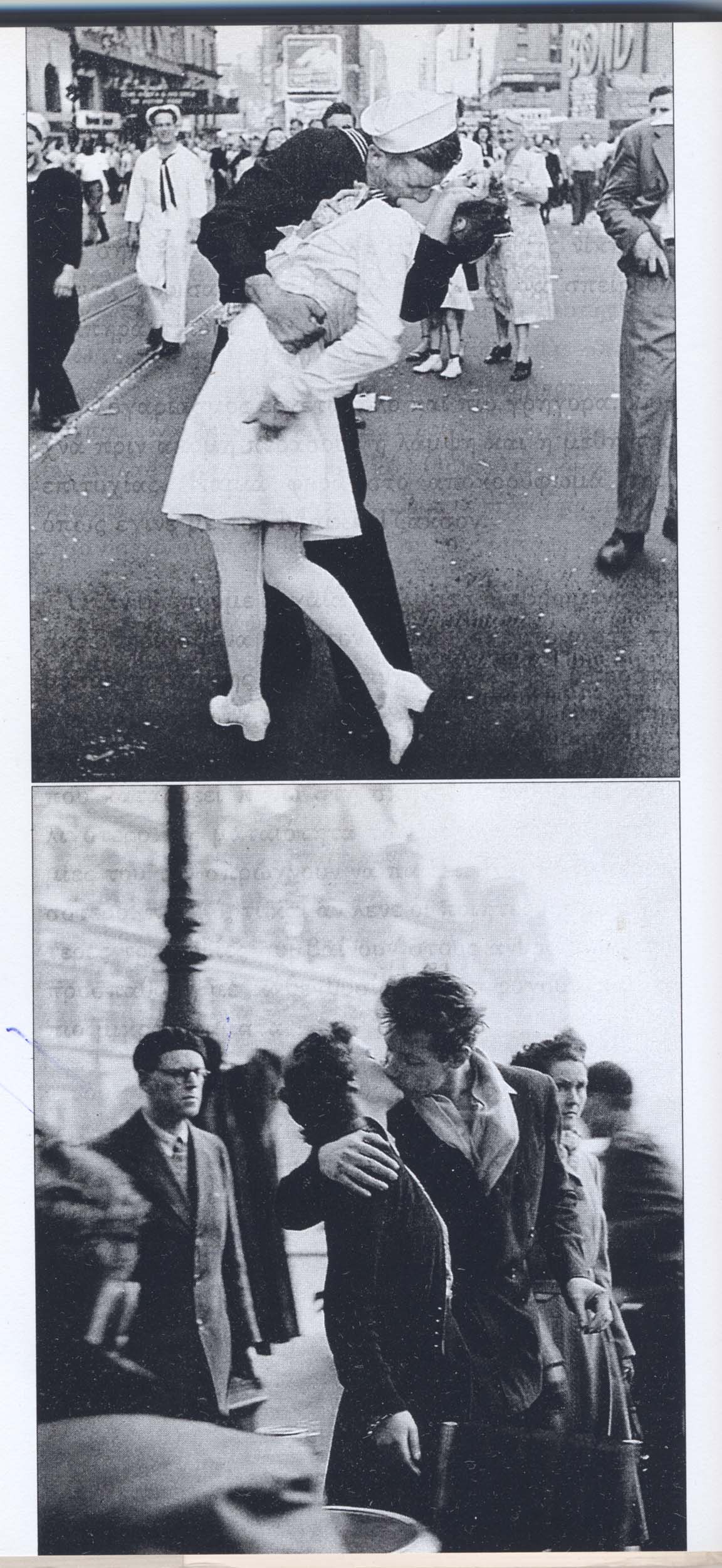

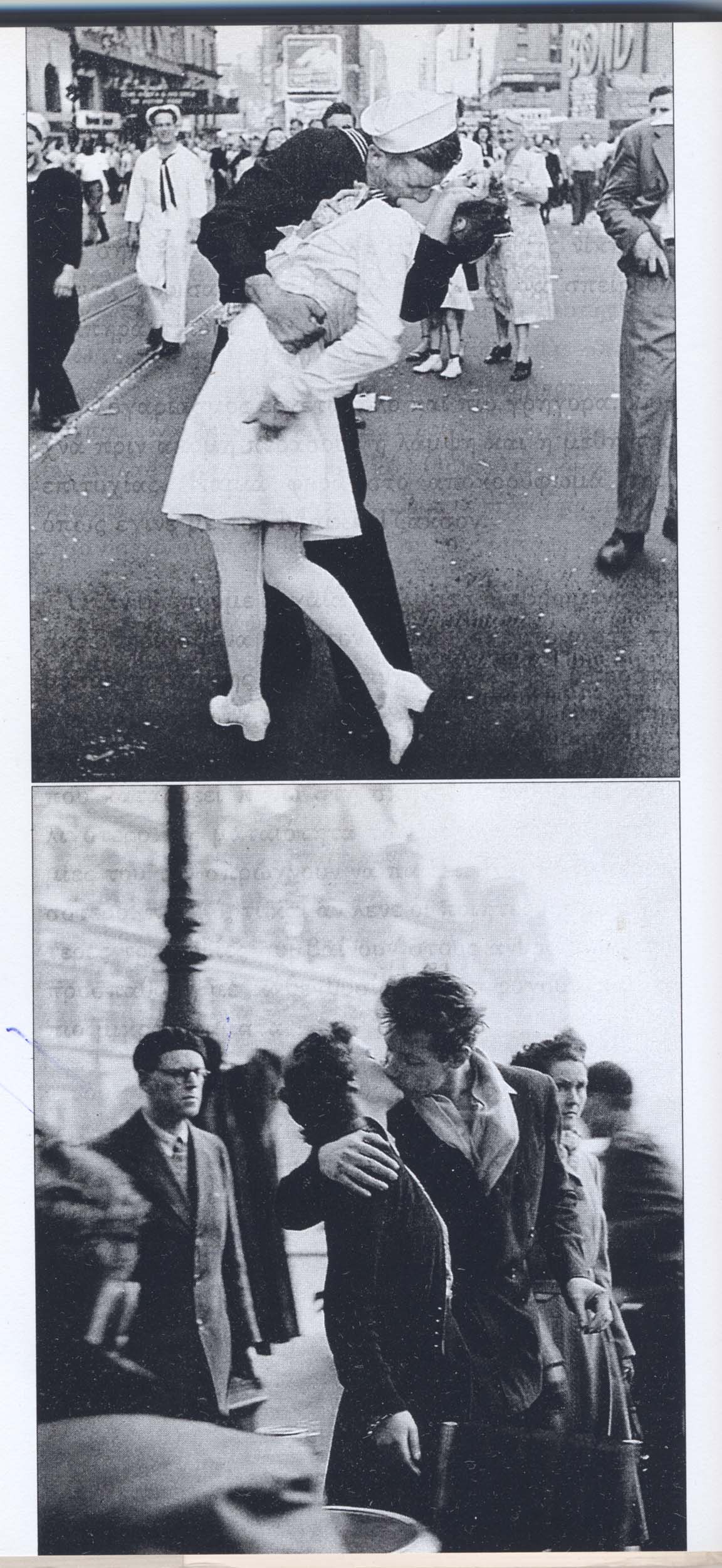

These are the two most famous kisses, both in the history of

photography and oh the 20 th century. The first was spontaneous; it was

shot by the photographer Alfred Eisenstaedt on Times Square in New

York, on August 14, 1945, the day Japan surrendered and the war

ended. The second kiss was given in 1950 on another square, Place de l’

Hotel de Ville in Paris. But its own authenticity is disputed; it is likely

that the photographer Robert Doisneau helped a little bit, one way or

the other, in the public expression of the two lovers’ passion. We shall

see later what this could mean.

It is of course no coincidence that the post-war period was

inaugurated by two kisses that became legendary and have since

decorated, as posters, the walls of millions of people; after a war that

had proved how easily human flesh could be reduced to an amorphous

mass of meat, free expression of the body became a maxim in the three

decades that followed. In an sense, it is not accidental either that in

both cases the kissing takes place on a square; more than ever before

love in the new era needs space to express itself, it wants to spread its

energy far beyond the private universe of the couple, to become the

force that will change the world.

A world that needs urgently to be changed, as the second picture

shows (and if only for this reason we should suspect this photograph of

being doctored). Let us pay attention to two frowning persons, the man

and the woman who frame the young couple. They are two of those

figures we meet every day on the street almost without noticing them.

But how graceless, stiff, dry, cobwebbed they look next to the kissing

couple! They are both staring in the same direction, but away from the

kiss: the joy of love is absent from their horizon. By contrast to the

bright faces of the two young lovers, their faces are grey (how not

suspect again that the photographer manipulated the picture playing

with the light?). The world these two passers-by represent is the aged

world of yesterday, deformed by the subjection to conventions. It must

be overthrown. Love will overthrow it.

In both photographs the most vivid, the most vibrating, the most

ecstatic part of the couple is the woman. She is the one who lends

tension to both scenes. Let us observe how the body of each girl is

curving like a bow, yielding to the male power, if one wants to see

these pictures through the glasses of traditional conceptions, but

prepared to correspond to its own passion, ready to emanate it

catalytic energy through a tremendous explosion, if we follow the

language of the pictures themselves. Also this is not accidental. The

woman was to be the more dynamic sex in the new era. It was mainly

her who would question the worn-out values of yesterday, who would

prove more adaptable to a world where the old roles were in

discrepancy with reality and the new roles demanded flexibility,

tolerance, empathy, freedom from obsessions. The dawning period was

the era of the woman. Maleness had finished with the Second World

War – its last, strongest and fatal convulsion.

The couple in the probably non-authentic photograph of Place de l’

Hotel de Ville is an authentic couple. The couple in the authentic

photograph on Times Square is a non-authentic couple; they are a

marine and a nurse who met as strangers in the crowd and kissed each

other in their enthusiasm over the end of the war. They never met

again. The nurse was identified long ago. She is still alive, being today

an old lady of seventy five. From time to time different men presented

themselves to her pretending to be the marine in the picture. But she

always detected them as swindlers by asking them what the man said

to her the moment he kissed her. All gave the wrong answer. Until, one

of the days I write this and the 50 th anniversary of the famous

photograph is celebrated, the marine too was at last identified. Also he

is alive, he is a retired policeman. He gave the right answer.

One is tempted to ask which of the two pictures is the most moving.

Most sentimental natures will perhaps prefer the authentic couple of

the probably non-authentic scene. Undoubtedly this picture, fake or

not, is a wonderful hymn to love, youth and beauty. But maybe its

perfection has something cool and remote. Besides, the thought that

the photograph may have been doctored stirs in us some vague,

unpleasant feelings up. If the couple was really in love, why should they

have needed the photographer’s urge to kiss each other? And if they

were ashamed to kiss each other publicly, because this was still unusual

at that time, what made them obey the photographer? Do we have

here the anticipation of a situation only too familiar to us now, the

invasion of our private life by the camera, which does not only record it

but forms it?

Personally I prefer the other photograph, the one with the accidental

couple. Even if it were not authentic, it would seem to me more

characteristic of our time: today it is mainly the accidental, unexpected

encounters that reactivate our zest for life and our passion. But since

the photograph happens to be authentic, I see in it also another, even

more comforting message: it is in the accidental, fleeting encounters

offered by the new era that we rediscover our spontaneity, the

genuineness and meaningfulness of our gestures which in our

everyday, established relationships are usually lost among purposeless

or too purposeful words.

Besides, the right answer to the question what the marine said to the

nurse, the answer that no scoundrel could think of, was: nothing.

(In: Greek Writers Today. An Anthology, vol. 1, ed. David Connolly.

Hellenic Authors’ Society, 2003. The excerpt was translated by the

author).

|